WARNING: Spoilers Ahead!

IN some Filipino and Chinese superstitions, the presence of green bones in cremated remains is believed to signify a person’s inherent goodness.

But for those behind bars, morality is far more complicated.

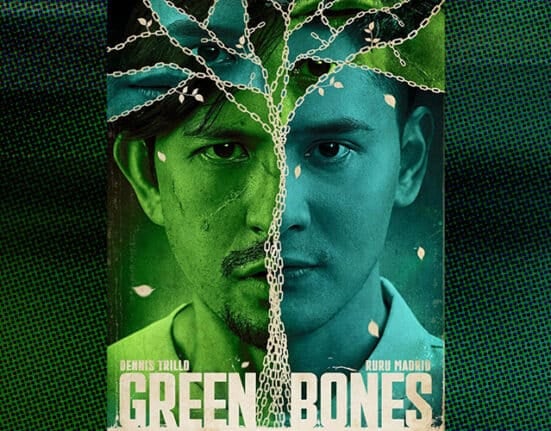

Netflix has officially added Green Bones, the 2024 MMFF Best Picture Winner, to its catalog. After watching it, I understood exactly why it took home the top prize.

Directed by Zig Dulay and written by veteran screenwriter Ricky Lee, Green Bones follows the story of two men: Xavier Gonzaga and Domingo Zamora.

Xavier and Dom couldn’t be more different. Xavier is the image of a straightbacked police authority— a rookie whose tragic loss forged his belief of a black-and-white outlook of right and wrong.

Meanwhile, Dom— or Dom Saltik as he was christened in jail— was everything Xavier despised. He was an addict, a thief, a “snatcher” that used to plague the streets of Manila.

But Dom’s ultimate crime was murder. He was sentenced to imprisonment after allegedly killing his own sister and her mute child.

The story begins with the collision of two very different worlds. Xavier is assigned as a Correctional Officer (CO) at San Fabian, a prison island located just outside Manila.

To his surprise, he discovers that the inmates on the island are treated with far more leniency compared to those in the Central facility. They were allowed outside the gated community, where they can sell their crafts and have minimal and guarded interactions with the residents.

Here, Xavier met the notorious Dom. He was embittered to learn that Dom was about to be given freedom due to his record of good conduct. He believes that Dom’s good deeds were all for show, and that a criminal is a bad person through and through.

But as Xavier gets to know the island and Dom Zamora more, he begins to question his long held beliefs:

Can a criminal really afford to change? Do they have a right to justice despite the blood staining their hands?

Green Bones’ beauty lies in its daunting presentation of character study. Through Xavier and Dom, it challenges our perception of morality as a binary construct, especially in a context informed by trauma and survival.

The self is a story, not a sentence

Green Bones was told in two perspectives— first of Xavier, then of Dom.

Even before he laid eyes on Dom, Xavier had already convicted Dom. Not just of murder, but of being a bad person in general.

He enumerated his reasons: Dom was an addict. Dom was a thief. And Dom killed his own flesh and blood.

So when he saw Dom’s name among the list of those who are to be paroled for good conduct, he didn’t buy it. He thought that something was fishy and set off to investigate.

He viewed Dom’s actions through the lens of suspicion. He learned sign language to guard Dom’s interactions and conducted a search operation in their cell.

But as the perspective shifted to Dom’s and we saw the world through his eyes, we realized that all his actions were read wrong.

Because Dom— presented by the film in a humanized version— was innocent.

He was an addict, he admits. He was a thief, he confirms.

But he did not kill his sister and niece.

In fact, as we watched Dom’s narrative unfold, he loved them dearly. Most especially, Ruth— his mute niece.

Dom just happened to be in the wrong place, at the wrong time, finding his sister’s body. He knew that the blame would fall on him because of his bad record as an addict and a petty thief. He was no hero nor a saint— he was aware of that— and so he tried to escape with his niece.

But when they were cornered, Dom was forced to choose between his own welfare and that of Ruth.

And it became his ultimate sacrifice.

He surrendered himself to the authorities and admitted a crime he did not commit. He told them that he threw Ruth’s body in the river, even though she was alive and well and could help testify for his innocence in court.

All these because he wanted to protect Ruth from her own father— a member of an influential syndicate and the one responsible for his sister’s death.

And this is where Green Bones shift from being just a prison drama to a meditation of moral identity and imagination. It lets us examine Dom’s personhood, his morality, and the events that led him to his choices.

Paul Ricoeur’s Theory of the Self becomes relevant in Dom’s character study.

In his philosophy, Ricoeur drew a distinction between two ways of understanding the self. The first one is idem which refers to the unchanging characters we assign to a person like “addict”, thief, or killer.

The other was ipse, which speaks to the evolving, relational, and narrative self. This is the self that is capable of change, of making promises, and of ethical responsibility.

Xavier only saw Dom’s idem identity. His rapsheet, his reputation. But when we, the viewers, are invited into Dom’s narrative—into his inner world—we are exposed to his ipse, the part of him that chose sacrifice over self-preservation, care over vengeance, and love over vindication.

This perspective presents us a more dynamic and fluid view of morality— one whose nature is not limited to the binary. Human beings are complex. To categorize us in narrow boxes such as bad and good is doing a disservice to that complexity.

Moreover, Ricoeur’s philosophy allows us to go beyond the rigid views of morality by acknowledging the possibility of redemption. It tells us that one action is not the end state of who we are as a person. That redemption is a continuous process of reauthoring one’s self. That the acknowledgement of past mistakes is necessary but should not be treated like a period that ends the story.

For Ricoeur, human beings make sense of their lives through narrative identity. This means that we are the stories we tell ourselves, and those stories can evolve especially through ethical reflection and memory.

Healing starts when you look someone in the eye

Xavier begins with a rigid moral frame: Dom is a killer.

During the film’s presentation of Xavier’s internal monologue, I was reminded of Javert from Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables. Like Javert, Xavier also held onto a rigid moral standard. Like Javert, he was an authority of justice.

For both of them, morality has a clear-cut and well-defined standard. Right will always be right. And wrong will always be wrong. And once you traverse the line that separates the two, there’s no going back.

But the difference between Javert and Xavier lies in how they respond when that belief is fractured.

When faced with the undeniable complexity of Jean Valjean’s humanity, Javert breaks—his entire worldview collapses under the weight of a goodness that doesn’t fit within his rigid definitions. He couldn’t acknowledge the goodness of a convicted criminal— and so he took his own life by jumping off the Seine river.

Meanwhile, Xavier bends. Not because he was not true to his principle but because he was exposed to the humanity of Dom. He realized not only Dom’s fault but his capacity for change and sacrifice for others.

This echoes Emmanuel Levinas’ idea of a Face-to-Face encounter.

Xavier and Dom were able to look one another in the eye. Levinas described this as the moment when you are confronted by the Other (another person). And in that encounter, you are called to respond. You are commanded— not by violence or force, but by the very vulnerability and humanity of the face— to recognize their life, their suffering, their needs.

The face, in this case, should not be treated in the literal sense. What it means is exposure to another person’s vulnerability. What it means is to recognize the infinity of the “Other”— that they cannot be reduced simply to stereotypes or categories.

In the film, we witnessed how Xavier’s rigid frame was challenged. We saw how his beliefs about human complexity evolved as he learned the context that informed Dom’s decisions. He recognized Dom’s desperation and his unconditional love for his niece Ruth, which he protected in exchange for his freedom.

Xavier learning about Dom’s story was what Levinas called a “moral interruption.” It was when the face of the “Other” (in this case, Dom) breaks your self-centered view. It means that when you look at another person, you’re not seeing them merely as an object. You’re dealing with a subject that demands ethical attention and empathy.

For Levinas, this should be the ground of morality. Not only rational rules as proposed by Immanuel Kant, or the maximization of happiness as forwarded by Utilitarianism— but as an uncomfortable and sacred exposure to another person’s humanity.

The true nature of morality

Green Bones doesn’t give us heroes, it gives us people.

It invites us to witness the stories of those separated from us by prison bars, not to excuse their crimes, but to remind us of their humanity. They are not so different from us. They feel pain, carry regrets, nurture hopes, and long for a future, just like we do.

Most importantly, Green Bones asks us to see morality not as a rigid set of rules, but as an ongoing exercise in empathy. It challenges the idea that justice is only about punishment or that morality is as simple as labeling someone “good” or “bad.”

It invites us to look closer—to sit with discomfort, to listen to stories we’d rather ignore, and to recognize the shared humanity in those we’ve been taught to fear or condemn. Morality, the film suggests, is not found in absolutes, but in the quiet courage to understand someone’s pain, even when it’s easier to look away.

The film doesn’t ask us to excuse harm, but to recognize that people who cause pain can also carry it, that they, too, are capable of change.

Because sometimes, doing what’s right begins with seeing people fully—not just for what they’ve done, but for who they’re trying to become.

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

Average rating 0 / 5. Vote count: 0

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?