FOR many Filipinos, the postwar years remain a blur—tucked between chapters of colonial conquest and wartime struggle, often overlooked for lacking the drama of foreign occupation and revolution.

But a new museum in Quezon City is quietly challenging that distance, reminding visitors that this era deserves just as much recognition as those that came before it.

Bahay Modernismo, which opened on June 12— just in time for the 127th Independence Day—, doesn’t commemorate war. It celebrates what came after: survival, recovery, and the stubborn will to live well again.

In a time when cities were still bruised and rebuilding, homes became more than shelters. They were symbols of resilience. Bahay Modernismo captures this through its architecture— a modest bungalow that is a reimagining of a typical 1950s Filipino household.

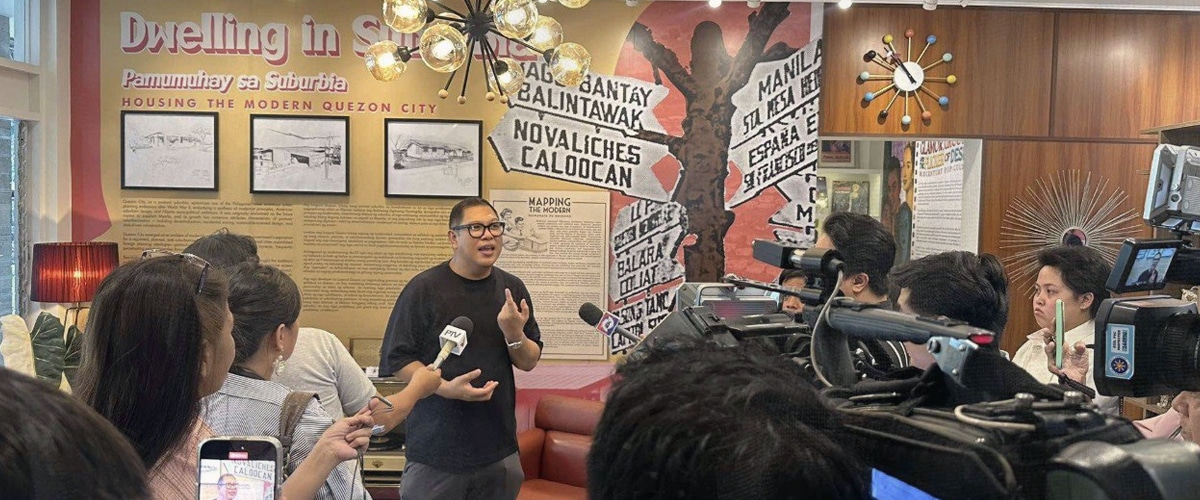

Museum curator and architect Gerard Lico shared during a media tour on Tuesday that Bahay Modernismo takes inspiration from the Aquino family’s old home at 25 Times Street in Quezon City.

It is a space once filled with the everyday life of democracy icons Ninoy and Cory Aquino, where they raised their children, including the late President Noynoy Aquino and his sisters Ballsy, Pinky, Viel, and Kris.

Its location— at the heart of Quezon City— is also a symbol of how the city became the country’s testing ground for its ideas of urban vision.

According to Lico, Quezon City was the new capital at the time. It was a blank slate in which to plan infrastructure design and urban development.

At the time, the modernism movement was dominant. It was a response to rapid industrialization, urbanization, and disillusionment brought by the war.

And so, it was also reflected in the architectural era of the time. This means that the many infrastructures were built to be functional and suited for mass production.

“Modernism was the style of survival and hope. Kasi yung modernismo walang dekorasyon, simple, madaling i-fabricate, so akma siya sa mass production,” explained Lico.

The bungalow style architecture of the museum follows this design. During the postwar era, it became the signature of the government-led housing projects.

The emergence of new household appliances, such as television, also influenced the floorplan of such houses.

“Television was the window to the world. It has become the center of home entertainment, with the classic transistor radio and vinyls, of course, and redefined how houses were arranged, and the furniture to suit family time,” said Lico.

While traditional heritage preservation in the Philippines often centers on Spanish-era churches or grand American colonial buildings, Bahay Modernismo breaks new ground by honoring something less romanticized but just as vital: the recent past.

It turns attention to the postwar years, a time when the country was rebuilding not just its cities, but its sense of self.

“Modern heritage is often ignored because it’s too recent. But it holds the memory of a generation, especially those born in the baby boomer era who grew up pampered in homes like this when parents tried to give as much comfort to their children while trying to forget the war trauma,” Lico said.

“Every item here has a backstory. They’re not just props, they’re memories passed down,” he added.

The museum welcomes visitors free of charge, and is open from Tuesday to Sunday, 9 AM to 4 PM, according to the Quezon City government.

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

Average rating 0 / 5. Vote count: 0

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?