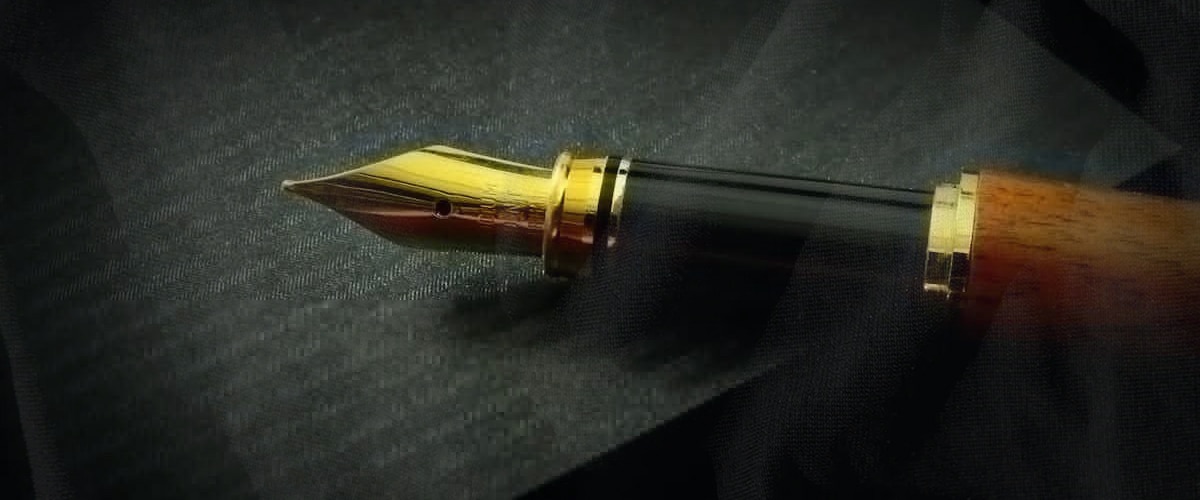

Many revolutions have begun, not with guns or clash of swords… but with a single word.

A single word can lead to a sentence—and that sentence can unfold into paragraphs of reflection, declaration, and manifesto, with the power to change minds and move hands into action. Real life accounts of resistance’s origins can often be traced not to protests in the streets, but to the quiet pages of diaries, journals, and poems written in hiding.

Censorship may silence a voice, but it can never erase the truth etched in ink and memory. Oppression has always feared the pen more than the sword, for while weapons can wound the body, words have the power to awaken minds, preserve memory, and ignite revolutions that outlive empires.

Stories— especially the written ones often smuggled between the margins— carry with them a certain kind of power: the power to resist and remember.

The freedom to write is never guaranteed

History has shown that whenever authoritarianism rises, the written word is among the first to be silenced. In many regimes, books are banned, journalists are jailed, and poets are forced into exile— not because they hold weapons but because they hold ideas.

The power of writing lies in its ability to express: a reflection, a critique, an idea that dares to challenge and offer an alternative to the dominant system and beliefs we live by. Literature—no matter how metaphorical, fantastical, or quietly written—becomes a threat when it gives voice to the silenced.

Even a simple sentence, scribbled in a notebook or whispered in a letter, can give shape to the abstractions in our minds—reframing how we see the world and, ultimately, influencing what we come to accept as real.

Rights, especially the right to write and express one’s self, are never permanent; they must be defended constantly for silence is what power demands when the truth becomes an inconvenience.

The Philippines: A nation written into being

During colonial rule, when guns and religion were used to enforce silence, the Filipino spirit found its more successful form of resistance not through force, but through ink and paper.

In the hands of the reformists and the revolutionaries, writing became a weapon— subversive essays, satires, newspapers, and novels that traveled across borders awakened people’s desire for freedom. Keen minds across the archipelago committed their thoughts to writing, embedding calls for justice in poetry, letters, and allegories that spoke louder than violence ever could.

The force of literature—its power to expose injustices rooted in lived experiences—stirred not only empathy among its readers but also a shared sense of outrage and awakening, a realization that the suffering of one Filipino echoed the suffering of many, and that together, change was not only possible, but necessary.

Among these, Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo ignited the public consciousness and gave the masses a mirror from which they witnessed the true face of their oppressors. Driven by José Rizal’s words, Filipinos began to understand themselves not as isolated victims of cruelty, but as part of a larger narrative—individuals with the agency to unite, stand in solidarity, and resist the injustices that had long been imposed upon them.

Out of these arose a new consciousness—one that dared to imagine a nation, and then fought to bring that vision to life.

Revolutions, after all, are not born from gunfires and flags, but from paragraphs and pages that dared to dream of freedom— and in the case of the Philippines, that dream became the foundation of a people’s identity, and the birth of a nation.

Writing is power, but also a responsibility

They say that writing is merely an expression, but I will argue that it is also a responsibility— what we choose to say, how we say it, and why we say it all matter. Under free societies, expression is a right; but in threatened ones, it becomes a duty— to speak not just for one’s self but also for those who can no longer do so.

Truth, after all, is not self-sustaining; it must be nurtured, protected, and repeated, especially in an environment where lies are louder and easier to believe.

Across history, those with the pen had been trusted not just with creativity but, more importantly, with clarity— what we write becomes part of a collective record, a history that might dictate our legacy to the generations to come.

Despite the accessibility of platforms today, expression without intention is just noise, and it is only when we learn to wield words responsibly that they begin to carry real meaning. Understanding how to read deeply, critically, and compassionately is just as vital— because it is through this that we absorb nuance, recognize manipulations, and reconnect with the humanity behind the symbols that the words carry.

The act of preservation is not solely the responsibility of institutions; it is also a personal task—something we must carry in the stories we pass on, the notes we keep, and the truths we refuse to forget. Even the smallest act—writing in a journal, recalling a memory, naming the unnamed—can preserve what history might otherwise overlook.

Remembering is an active choice, especially in times when forgetting is easier, encouraged, or even enforced. To preserve is to resist disappearance; to express is to recognize the power of your voice.

Every story carried forward becomes a thread in the fabric of collective memory, a protest against oblivion. And in that protest, writing becomes sacred— it is not just a practice anymore, but a promise.

Some will argue that writing is a luxury, but in the face of oppression, it becomes one of the last tools of defense.

Our task, then, is not just to write, but to do so with care—for those before us, and especially for those who will come after.

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

Average rating 0 / 5. Vote count: 0

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?