YOU’RE scrolling through your feed when a post stops you cold: ‘Breaking: Jackie Chan passes away at 70.” Your heart sinks as you think of what his loss means to the industry. Without hesitation, you share the post on your Facebook page, and soon your friends share it too.

But minutes later, you see another post debunking the claim— Jackie Chan is alive and well, just like he was the last time the rumors made this round.

Most of us, at one time or another, have had a similar experience like this— falling victim to fake news. Whether it’s a celebrity death or a misleading headline, it’s all easy to get caught up in the frenzy and share before verifying.

More so, in this age of social media. Misinformation thrives on our quick reactions, turning even the most skeptical among us into unwitting participants in its spread.

This doesn’t come as a surprise since the architecture of social media is built on engagement, not accuracy. This creates a perfect storm for fake news to thrive, where they can exist along with the verified information.

Although social media platforms put efforts in mitigating fake news, it can’t be denied that most of them are made to profit off of it.

Outrageous claims, sensational headlines, and emotionally charged content are algorithmic gold for platforms that prosper in engagement counts.

While this may line the pockets of the billionaires who own these platforms, it comes at a significant cost to society, fueling polarization, spreading confusion, and eroding public trust.

Gen Zs are now witnessing a world where the truth can barely compete with the clickbaits. What would happen when it can’t anymore?

Defining fake news

In 2017, ‘Fake news’ was named Word of the Year by Collins Dictionary, an influential and well-established printed and online dictionary of the English language.

According to Collins, the usage of the word surged in 2015 and has remained a staple in our vocabulary ever since. Many attribute its prevalence to the rise of social media, where it continues to thrive.

In the Philippines—dubbed the ‘Social Media Capital of the World’—fake news runs rampant, mirroring the country’s heavy social media usage. In 2022, Pulse Asia reported that 90 percent of Filipinos have been exposed to political fake news, and 86% of those believe that fake news is becoming a problem in the country.

This raises a crucial question: what exactly is fake news—or what do people perceive as fake news? We’ve seen politicians label unfavorable information as ‘fake news,’ but does it simply refer to anything that challenges our beliefs?

To answer this question, republicasia consulted University of the Philippines Diliman Associate Professor Danilo Arao. Professor Arao, from UP Diliman’s College of Mass Communication, is also the current editor of Media Asia, a highly regarded international refereed journal.

“There are various academic definitions of fake news and in fact, there are types or typologies of fake news, but what’s common with the various academic definitions is that there is a consensus that basically fake news is the exact opposite of journalism which is truth-telling,” explained Prof. Arao.

He said that even if the ‘fake news’ is packaged to appear like a journalistic output (which it often is) like a news article or a news television segment, if it promotes lies and inaccurate information, it can still be considered as fake.

“As the term suggests, fake news has to do with lies, misinformation, and disinformation. In the context of journalism, if journalism upholds truth-telling, fake news would be all about misinformation which may be unconsciously done, or disinformation which is something that’s consciously disseminated even if people behind such lies know that it’s very, very far from the truth,” he stated.

The fake news industry

Although the word ‘fake news’ had an upsurge in usage during the age of social media, it is not a new phenomenon.

“Of course, I have to qualify that fake news is not really new. It’s not new because even before the internet there are efforts to engage in what we call— well, it’s not called fake news yet— but the term black propaganda was being used to put certain people or certain events or certain groups in a negative light,” said Prof. Arao.

Black propaganda refers to the misinformation or disinformation that is intentionally designed to harm an enemy’s reputation through deception and manipulation of public opinion. It is typically attributed to a false source, relying on fact distortion and fabricated evidence.

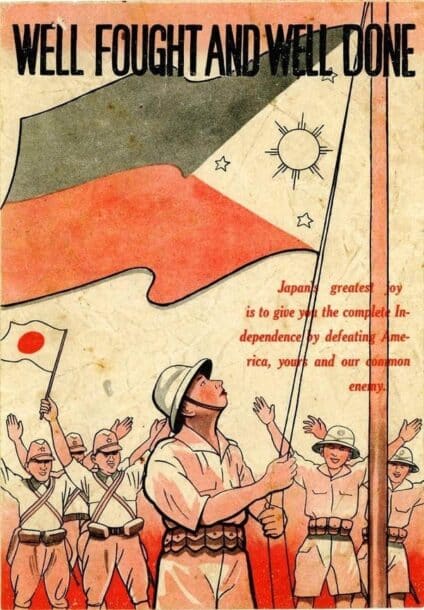

We need not go far from Philippine history to see this kind of machinations. During World War II, for instance, the Japanese used radio, newspaper, film, and theater to reengineer the Filipino consciousness in their efforts of colonizing the country. In fact, the whole “Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere” campaign by Hirohito or Japanese Emperor Shōwa is now viewed by historians as a great propaganda to excuse their occupation and colonization of Asian countries.

A Japanese poster propaganda in 1942. Photo Courtesy: Pacific Atrocities Education’s Facebook Page

But with the rise of social media, the nature and dissemination of black propaganda have also evolved.

“It has become worse with the advent of social media. What is supposed to be an instrument that would empower ordinary people to disseminate truthfulness has become weaponized for the exact opposite of what it is supposed to be intended for. So you can say that the internet—or even social media to be more specific—has become some sort of a double-edged sword,” said Prof. Arao.

According to him, fake news could either be misinformation or disinformation. Misinformation occurs when the fake news peddler is unconsciously giving out information that is not accurate or correct.

But Prof. Arao said that the majority of ‘fake news’ we see nowadays on social media are caused by disinformation, or the conscious dissemination of false information.

“The closest process between misinformation and disinformation would be the one that begins with the letter D because another study would prove that fake news has become an industry. In other words, it’s not something that’s done by people who have nothing better to do, but rather people who can earn from such fake news peddling. No thanks to the current setup in various social media platforms where virality is paid off through monetization,” he said.

“In other words, it doesn’t matter if the content is true or not as long as it’s viral or as long as there is a lot of engagement.”

The prevalence of fake news in the country has now impacted its several facets, particularly the people’s trust in the government. Influencers and content creators delved into politics that’s causing extreme polarization among Filipino voters.

The effect is so undeniable that it prompted the legislative branch of the government to spring into action just recently, when the Representatives summoned 40 social media personalities to the House.

“It’s either they are clout chasing or they just simply want to monetize their content. Therefore, they want to make something viral or the most sinister thing perhaps is that they are paid by certain people or groups to spread lies against certain individuals or certain groups. Sometimes, they want to prop up the image of a certain individual or a certain group in exchange for monetary rewards,” explained Prof. Arao.

“There are case studies where some content creators and influencers can get five figures just for posting about a certain individual or a certain group. That’s the reality when it comes to disinformation. That’s why it becomes financially attractive for some.”

The ‘troll farms’ are also a recurring problem in the Philippines. These are organized groups of individuals or automated accounts (bots) that create and spread disinformation, propaganda, or inflammatory content online to manipulate public opinion. They often work in coordination, posting messages, comments, or fake news across various social media platforms to amplify specific narratives, attack opponents, or sow discord.

Although efforts are being done to mitigate these troll farms, such as the filing of House Bill (HB) 11178 or the Anti-Troll Farm and Election Disinformation Act last December by PBA party-list Rep. Margarita Nograles-Almario and Davao Oriental 2nd District Rep. Cheeno Miguel Almario, we are still far from having it under control.

It doesn’t help that social media platforms such as Facebook, X, and the others are in control of billionaire businessmen whose main goals are to earn profit.

“The tendency of social media platforms would be to literally pay content creators for doing such things – which is unfortunate,” said Prof. Arao.

How to combat fake news

Fake news is an ominous force that’s been taking over not just social media platforms but aspects of our lives. But how do we fight it?

Professor Arao gave several solutions— for the consumer, the producer, and the social media platforms.

“The solution to combating, fighting fake news would be media literacy and media education. Media literacy would be a major factor,” he said.

This is for the consumer of the information. One must learn to be actively critical of the information they see, instead of being just a passive recipient.

“Number two, self-regulation in the media. We have to strengthen our ranks. Make sure that we’re able to have a more systematic manner of fact-checking, for example.”

This one is for the producers of information. Like what Prof. Arao said before, misinformation can also cause fake news, whether you are conscious of this mistake or not. Being actively aware and critical of the information you’re publishing could help build your credibility against fake news.

“And number three, we should pressure social media platforms to exercise what we call responsible gatekeeping. Just like what news media organizations do,” added Prof. Arao. But he quickly clarified that gatekeeping is different from censorship, which would cause issue on the media’s freedom of expression.

“I mean, gatekeeping, if practiced responsibly, is not censorship. We have to make such a clarification because people or those who are not media literate enough or those who are in denial they would tend to argue that censorship. That’s not true. Censorship is usually state-sponsored. Gatekeeping is an integral part of any operations in the newsroom,” he explained.

“Anybody who practices journalism is subjected to gatekeeping because you cannot allow anarchy in the newsroom. You have to filter which is true. You have to choose which articles or which issues should be discussed or should be part of the news cycle. That’s what Mccombs and Shaw termed as Agenda Setting Theory, right? You cannot set the agenda without gatekeeping,” he added.

A final advice

Prof. Arao, a veteran professor and journalism researcher, has advice for the younger generations.

“Today’s generation should fight fake news. They should be able to properly discern the lies. Usually if it’s too good to be true, it’s too good to be true. We have to engage in multi-sourcing,” he said.

“If one news media organization would claim one thing but it’s not echoed or covered by the other newspaper organizations, I’m not saying that it’s not true, but we have to check why this is so. Is it an exclusive report? If it’s an exclusive report, how did it come about? There has to be a way to verify the information.”

He emphasized the importance of doing research— something that is often frowned upon by many due to its difficulty.

“For today’s generation, the hunger for research should be there. I don’t see anything problematic for today’s generation, to be media savvy, to be watching videos for example ,or being more biased for social media content,” he said.

“But that particular bias should not compromise the hunger for knowledge that can be provided by books, by the so-called legacy media like radio or even newspapers.”

In an age where misinformation thrives, the younger generations hold the key to restoring truth and accountability.

By fostering critical thinking, practicing multi-sourcing, and embracing the hunger for knowledge, they can become the front line in the fight against fake news—a battle that requires not just vigilance but also a commitment to seeking the truth, no matter how challenging it may be.

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

Average rating 0 / 5. Vote count: 0

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?