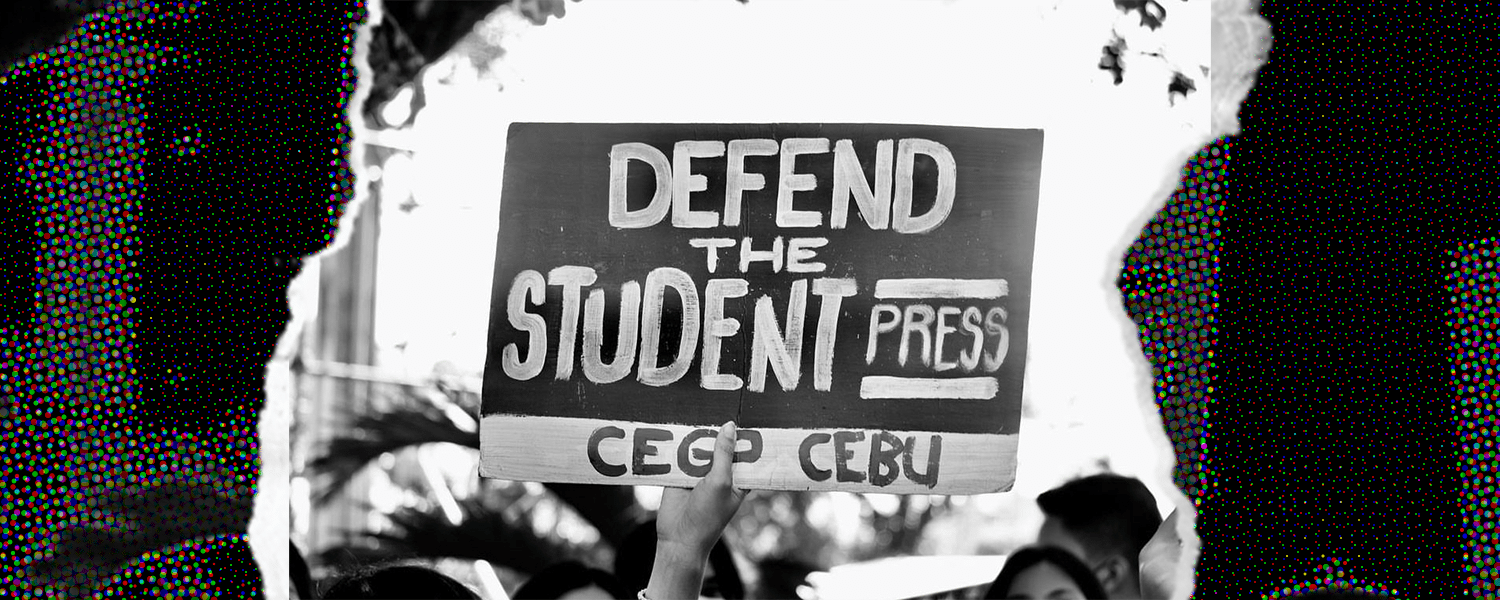

IN 2022, the Philippines ranked the seventh most dangerous country for journalists, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists. This is due to the fact that each year, journalists are killed, most often for just doing their job. From 2000 up until 2022, 140 journalists had their lives mercilessly taken away.

Even those who aren’t even out in the real world yet – student journalists simply writing for their school publications – live in constant fear of violence, trolls, and red-tagging. At this point, it seems to be something to be accepted, perhaps even becoming a part of their routine: wake up, brush teeth, get comments saying they deserve to die, make morning coffee.

Many student journalists have reported being attacked online by trolls, especially whenever they publish articles that call out the injustices the government has committed. A number of student organizations are also being red-tagged, and even more are losing funding.

22-year-old Joash Malimban, a Multimedia Journalism intern for Fyt Media and a photojournalist for UP Diliman’s Tinig ng Plaridel, recalled an incident wherein his team had been a victim of an attack. He explained that at some point, the blog Thinking Pinoy attacked Fyt Media, claiming that the latter had taken down a post on Facebook when in reality, Meta had simply deleted the post because it apparently violated certain community guidelines.

The post stayed up on Twitter and Instagram for the duration that this was happening. Even so, trolls started to attack Malimban’s publication.

“That’s a grave effect of misinformation, lalo dun sa mga tao na talagang ang lalawak ng platform pero wala silang pakealam sa consequences ng pagkakalat ng maling impormasyon,” said Malimban.

Common misconceptions

Perhaps the image that many people have of journalists has become glamorized by the likes of Rory Gilmore from Gilmore Girls or Josie Geller from Never Been Kissed, because some think that it’s easy work; just write a couple words and blammo! You’re done.

Malimban – who is often in charge of posting videos on Fyt Media’s TikToks – even shared that he often finds comments on his publication’s social media pages stating: “Nagbabasa lang naman sila ng mga prompter. Bakit kailangan niyong hangaan yung mga journalist na ‘to?”

The reality of it is that journalism is hard; it’s hard, but it’s worth it.

21-year-old Chelsea Visto, a fourth-year student at UP Diliman and a writer for Tinig ng Plaridel, first joined the organization back in 2020. She’s been an active member for the past three years, moving up from Features staffer all the way to Features editor as of 2023.

Despite this, there are still times when Visto experiences immense burnout, especially when deadlines are near, or when things aren’t really going her way. For her though, that’s just a part of the job.

For Visto, being a journalist means getting to see the world through the eyes of others, living vicariously through the stories they share.

“At one point, you will start to find meaning in the most mundane moments of life — because you realize that the mundanities of your life could be a privilege for others,” she said.

“Journalism is all about exploring life beyond your bubble, [and] that excites me,” she added.

Meanwhile, when covering events, Malimban often has to get up by 6 a.m. and then leave by 7 a.m., commuting by LRT from Katipunan to Manila to take photos of whatever’s been assigned to him. Often, he takes photos of mobs, events in UP, and the like.

During his coverage of the UP President’s Selection, he finished at 6 in the evening. When it comes to mobs, he has to work from 8 a.m. to 12 p.m.; that may seem short to some, but that’s five hours of nonstop picture-taking. That means a hell of a lot of moving around and always being on your feet to ensure that you never miss an important moment.

Malimban and Visto’s school publication also does not give them financial compensation whenever they have to cover events, even if they are with the official news organization of the College of Mass Communication at UP. Their transportation fee, their food allowance – all of these come out of their own pockets.

Though this cycle may be tiring, Malimban recalled one time when, for his internship at Fyt Media, he was granted the opportunity to listen to renowned journalist Kara Davis.

Loosely quoting her, he said: ““Hindi ka pumasok sa journalism para maging mayaman. Hindi ka pumasok sa journalism para madalian. Pumasok ka dito kasi you have the talent, you have the skills to give voices for the people.”

That is what journalism – campus or otherwise – is about: allowing yourself to become a vessel for voicing out the needs of others. If you’re in it for the glitz and glam, forget it.

The horrifying reality

More than the glamorization of life as a journalist, though, there is a matter more dangerous, more pressing, that has only worsened in the Philippines over time: that of red-tagging and state violence.

Tinig ng Plaridel, like Fyt Media, has also been a victim of trolls in the past. Visto refers to the issue as a “troll infestation,” wherein people were making several threats and insulting comments under one of its posts. Following the incident, its Editor-in-Chief and Associate Editor-in-Chief were then red-tagged.

“[It] shook me to my core; I’ve seen troll attacks on prominent opposition figures, but it feels incredibly different experiencing those attacks yourself,” she said.

And these dangers don’t just exist online. Malimban, as someone who frequents mobs for photo and video coverage, has had his fair share of being shaken up – only this time it was done by the very people sworn to protect him.

“May isang beses, nagtanong sa’kin [yung pulis] nung first time ko mag-cover sa Mendiola kung saan daw ako estudyante,” he recounted.

“Usually ganun yung mga mae-encounter mo as a student journalist kapag magco-cover – lalo na sa mga mob – kasi alam naman natin yung pagiging… ano ng state forces… when it comes to [that.]”

And the experiences of these two mirror what numerous other journalists are going through at this very moment: the threat of violence, or even of death, simply for telling the truth.

It’s not unusual for students to be targeted anyway; in the fight to silence honesty, no one is too young. No one is safe.

This much is evident from the 2001 death of Mark Welson Chua, an ROTC cadet studying at the University of Santo Tomas who, after exposing to The Varsitarian the heinous acts of corruption, extortion, and bribery happening in his unit, was found dead days later, body floating in the Pasig River.

And outside of school, the dangers could be seen in the killing of radio journalist Percy Lapid, who often spoke up against the injustices happening within the government. His bravery to spread the truth is what led him to get shot just while he was about to head off to work.

These dangers were also apparent during the media blackout that happened during the time of Martial Law and the deaths of thousands that we know about, and those we don’t know about, and the subsequent killings that took place in succeeding administrations, which are taking place even now.

The toll only continues to go up as the years go by. If there’s anything to take away from the life of a journalist, it’s that it’s definitely not for the faint of heart.